Almost a year ago I began to consider the idea of adding a neck pickup to my Berlin-II model. The greater tonal possibilities would be complemented by better acoustics (more on this below), and what was initially vague started to turn real.

I decided that the soundbox would be similar in size and shape to my 15-inch guitars, instead of the non-conventional design of the Berlin-II. And, as it was not possible to open a hole for the second pickup (the acoustics would be totaly lost), I decided that both pickups would be the floating type. I had done this before for several guitars, using plastic pickguards with an internal skeleton of FR4 (fiberglass). All my designs for this new model departed from this idea, inspired by the old Gibson McCarty pickguards. I decided also that all the controls would be on the pickguard and below the pickups, something that I had done before.

The neck was going to have the very light machines from Gotoh, embedded into the peghead as in the Berlin-II model. Many of my guitars with this size and shape have 16 frets out of the soundbox, but I have had a lot of problems trying to find quality cases that fit. The smaller peghead almost let me put sixteen frets out, but in the end I decided to leave fifteen so I could use a Hiscox case. Unconventional, but justified.

The shape of the soundbox is basically the same as in my Jamaica guitars. The back starts the same, but the final graduations are much much lighter. The top is different, both in the design of the soundhole (Jamaicas have f-holes) as in the graduations, maximum arch and the shape at the cutaway area. The bracing would be much lighter also.

I was making two guitars of this model when I received a call from an Italian player. He wanted something different, but he liked the idea of this new model, and somehow I got him mixed up in this project. The bad news for me was that I could not use the two necks that I had already made, as he wanted a short scale of 24 3/4″ and a wide nut of 1 3/4″.

My client didn’t find appealing neither the plastic pickguard with the pickups on it nor those peculiar scrolls above the pickups. He preferred a wooden pickguard (who wouldn’t?) and nothing about scrolls. And here came the best idea in this design, the pickups supported by the pickguard skeleton. Inspired by my client! I like that guitarists say good things about my guitars, but I absorb and keep obsessively the critics and suggestions. Sometimes these things have been deciding my moves for years! Then I improved the attachment of the pickguard to the guitar, and the controls. This design didn’t come rolling; I had many problems, but in the end I had something good. Very good, in fact. I consider that this part is the greatest innovation for this guitar model. And that’s why I asked my client to give me a name for it, and he said “Siracusa”, which is perfect.

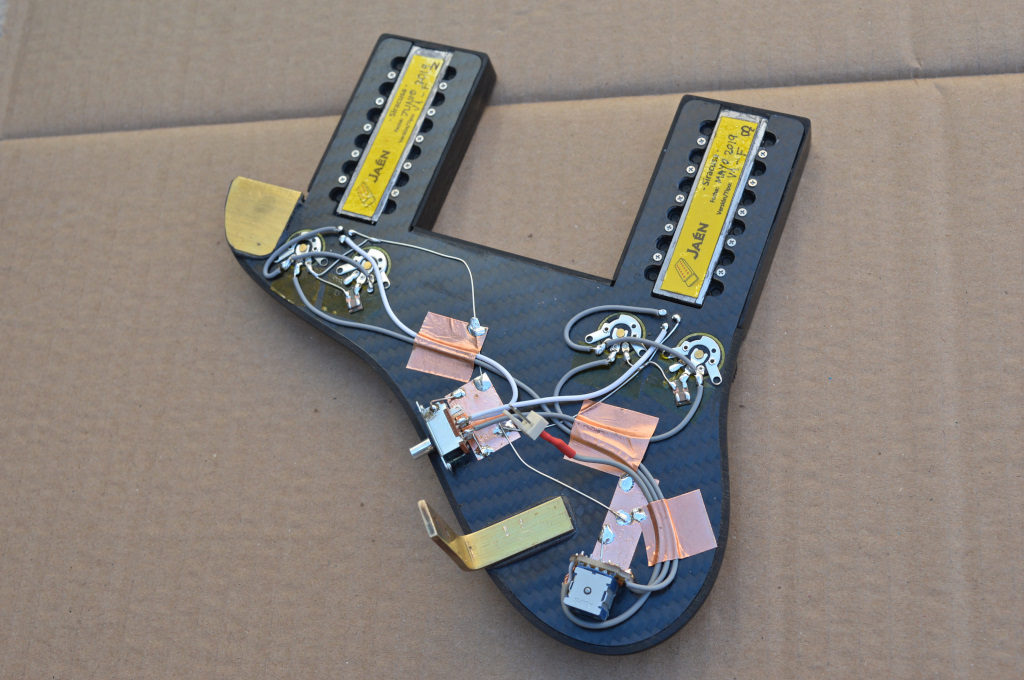

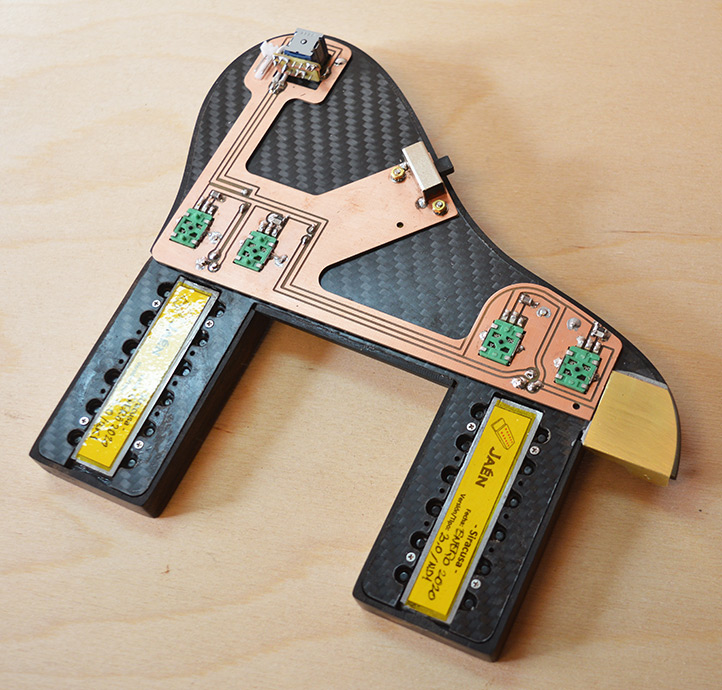

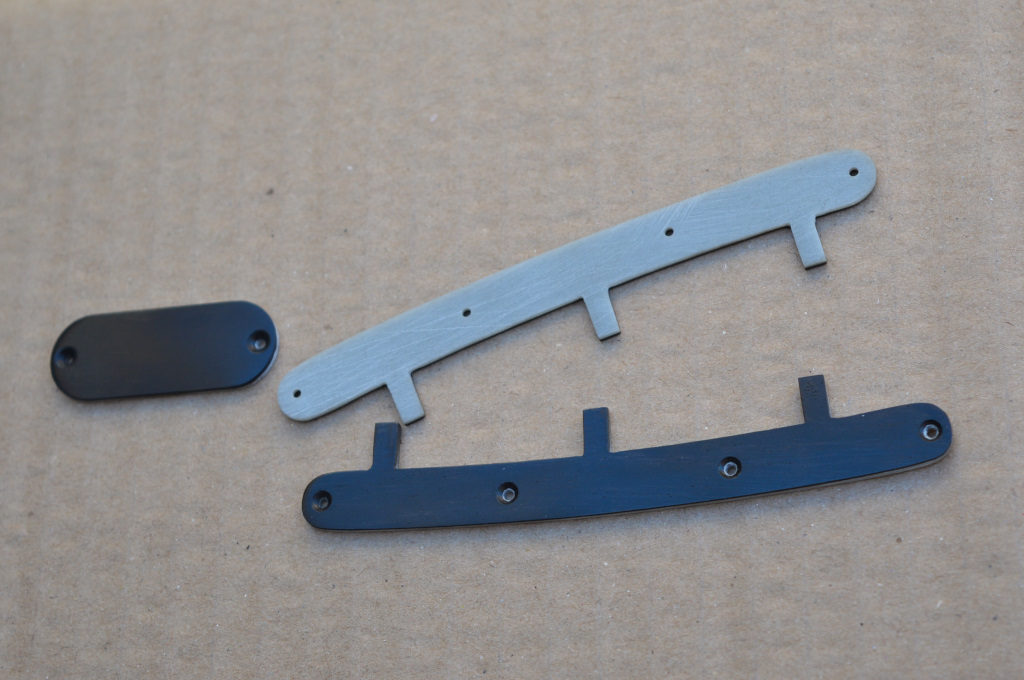

The pickguard is a structure with a carbon fiber skeleton, 2 mm thick (I discarded a FR4 version that was not stiff enough). It is embedded in a hollowed out ebony piece, which is the external part, the only one visible. The pickups are joined to the pickguard, which integrates the pots, the pickup selector and a switch that we’ll see later:

The pickups are uncommon, no matter how you look at them:

They are high inductance units (I don’t like thin-sounding pickups, and almost all commercial floaters are like that). They have two rows of polepieces, so you can adjust them for bronze strings or other oddities. They have three terminals, as seen in the pickup below. They are made from a piece of ebony, and have recesses for the potentiometers that resemble a the “ears” of some old P90 pickups. They are attached to the pickguard with screws:

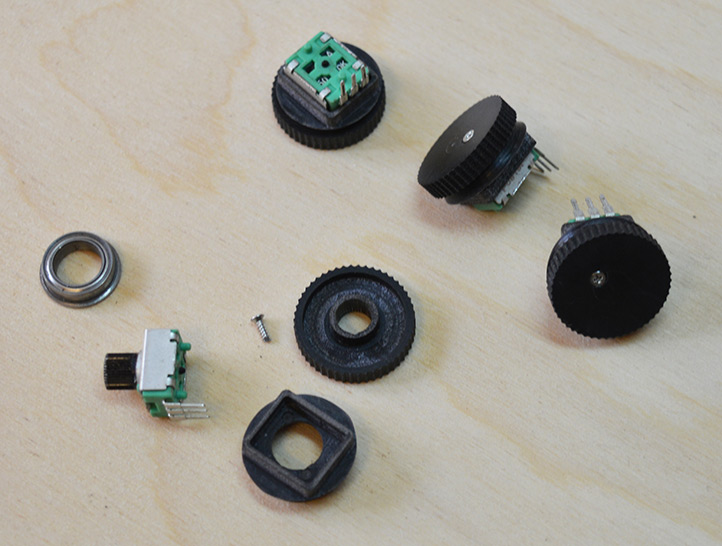

The pots are inserted in small pieces that set their thumbwheels above the surface of the pickguard:

The thumbwheels (on the left, blurry, one upside down) have bearings. They work smoothly.

This is the circuit:

I used SMD capacitors, with C0G dielectric. I don’t believe strange things about capacitors, but I prefer to use dielectrics that are stable and don’t have any piezoelectric characteristics (most ceramics do).

The pickup switch is very small, but it is a quality component. I made a small printed circuit for it, so that the connections are clean and reliable.

The additional switch cuts a coil for each pickup. In that situation, the guitar has two single coil pickups. However, most designs cut the same coil for both pickups, but in this one I decided to cut the inner ones. This leaves a “North” coil active at one pickup, and a “South” coil active at the other. So, if this switch is set to “Single Coil” and the pickup switch is set to the mid position then you’ll have a parallel humbucker.

Note: I have been improving this design for every Siracusa that I have built. Currently (April 2020) I use a thin printed circuit board and different potentiometers, that are smoother and with a much longer rotational life (100.000 cycles instead of 15.000 of the units shown above):

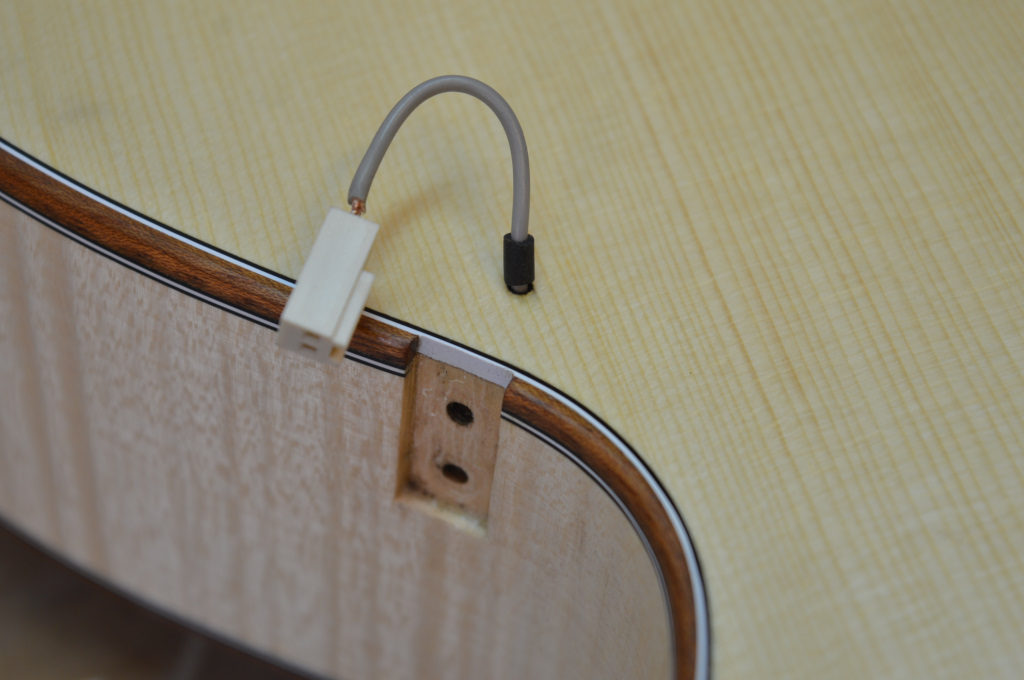

The attachment of the pickguard is made at two points. This recess is for the one at the neck:

There is a brass piece in the pickguard that plugs into it:

The other point is at the side. The usual system is very weak, and this pickguard is heavy, so it needs firm supports. This guitar needs a more elaborate design:

Note that the output cable goes through a small hole near that attachment point.

By now you must have realized that the finish on this guitar is not a heavy glossy lacquer. It has an oil-wax finish (Osmo) with a much more natural look and many other great properties.

This second attachment point has nut inserts inside the soundbox:

The soundbox is made of the usual archtop guitar woods: European spruce for the top and curly maple for the back and sides. I mentioned that the back is the same as in my Jamaica guitars, but the graduations are much lighter for the Siracusa. The top is different but, just as the back, it is carved very responsive. The braces are in “X”, and they cross off-center to compensate for the asymmetrical soundhole:

The design of the neck is laminate and, as I already commented at the beginnning, it has Gotoh Stealth machines, amazingly light:

The covers are made of ebony, reinforced with FR4 inside. This design permits to use thin wooden parts, tough enough for their job:

The frets are made of stainless steel, and the fretboard is curly ebony. The curl in ebony is extremely hard to appreciate, even when it is strong, but we leave it here for the connoisseurs.

Regarding the fittings, the bridge is the type I was using for my latest Berlin-II guitars, except this is higher. This leads me to comment a difference between these two models: the Berlin-II has the fretboard glued directly to the top while the Siracusa has an extension, a piece usually found on archtops that gives more freedom when deciding the breakthrough angle, the bridge height and other important characteristics.

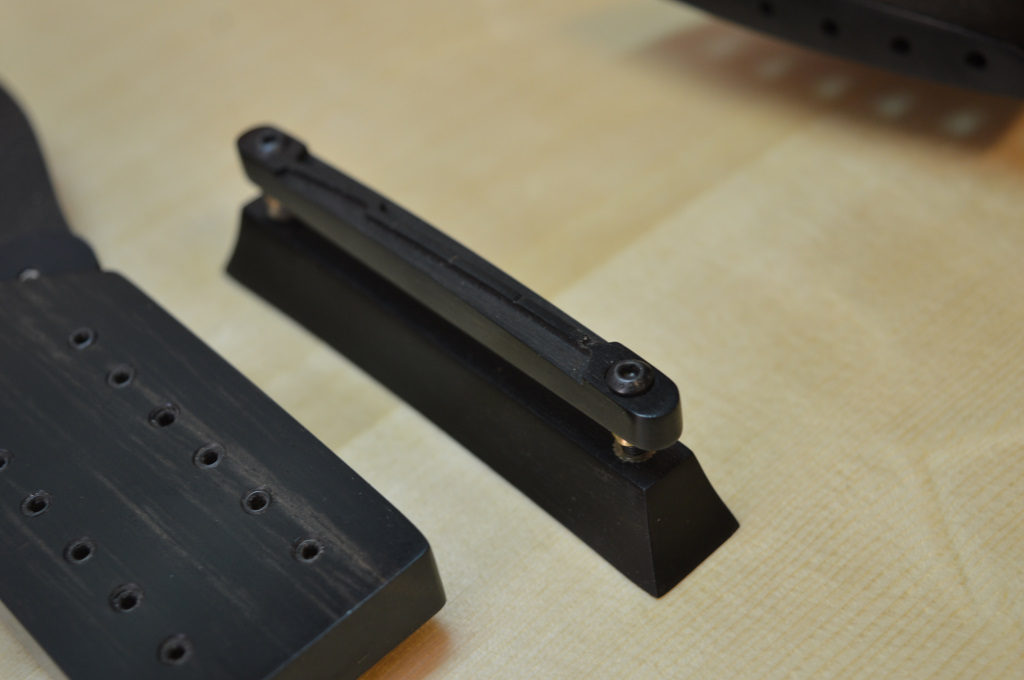

The bridge is quite small:

The foot is hollow, very light. The saddle is made of ebony externally, but that is just the “skin”. It has a core of pultruded carbon fiber inside (pultruded means that all the fibers are oriented the same). The adjustment mechanism is smaller and lighter than the conventional thumbwheels.

Regarding the tailpiece, I decided to modify it. Instead of the usual pieces that I use to ground the strings, visible from the outside, I thought it would be possible to hide them inside. Then I thought I could improve the shape, and the result was elegant, and I’m not talking about aesthetics only, but also functionality, ruggedness and construction. Without any doubt, the tailpiece was another high point in this design:

That photo shows the brass rings that ground the strings. They can be seen here at the other side:

They are completely inside the tailpiece. Apart from these technical details, this tailpiece looks amazingly beautiful to me, without any doubt the best that I have designed. The perfect addition for a guitar like this.